OTR, Take 59: Gus Cannon - Walk Right In

I'm thinking about recording McNugget's early morning screaming and using it as the ring on my phone's alarms. Nothing else has been able to consistently wake me when I don't want to wake up. In college, I slept through fire alarms. I have yet to find an alarm that I can't ignore. Upstairs, I have an alarm clock that has a large buzzer that I place under my pillow. It raises a ruckus, but generally, it's Audra who gives in.

"Will you turn that damned thing off?!"

But the little monk's cry? My eyes shoot open and I have a difficult time falling back asleep, even if I don't entirely wake up. The Walking Dead is really just a show about parents of young children. (I've never watched the show, so this is pure speculation that feels more correct than the actual premise of the show.)

McNugget woke me up around 5 this morning and I've been in a bit of a haze. Tried going for a walk with Clare to clear some of that muddiness, to no avail. So let's try a more acute tincture: the banjo blues.

When Audra and I first met, I lived with my youngest brother. I'd been recently divorced and our place in Lawrenceville was nice, but definitely a bachelor's pad. The place was overrun with books and musical instruments. (I guess our house now is, too – but it's less chaotic now.) My brother and I had a drum set, four bass guitars, three acoustic guitars, six electric guitars, a keyboard, four amps, and a banjo.

For the most part, I think Audra found this a bit much, but perhaps slightly charming. At least peculiar enough for a quasi pat-on-the-head "that's cute." But the banjo was something she didn't understand then and to this day fails to appreciate. She does not see the appeal of this strange African instrument that hillbillies have adopted. Over the years, I've given away the drum set, but I still have the banjo despite her pleas.

When she saw how excited I was at a new record purchase, she asked what I got. "There's a reissue of a rare Gus Cannon album he recorded for Stax when he was like 90 years old!" None of this seemed to her to justify my excitement.

I wish you could have seen the excitement-to-crestfallen transition in her face when I told her it was old-time banjo blues.

As I was searching for the photo of the music room, I ran across this old daguerreotype of Audra and me in the before times. Look at us! We look so alert and happy! It's like 11 pm!

Gus Cannon was born on a plantation sometime in the second half of the 19th century. We don't know exactly when. It's good to remember that, not long ago, basic records like birth and death weren't always well kept – especially for certain classes of us. In an age where we are overrun with data (a ton of information, little knowledge, and less wisdom), it's worth stepping back to understand that this ready access to data doesn't necessarily help us understand anything, even if it gives us the illusion of knowing things. Anybody who's sat in a leadership team meeting puzzling over complicated dashboards knows what I mean.

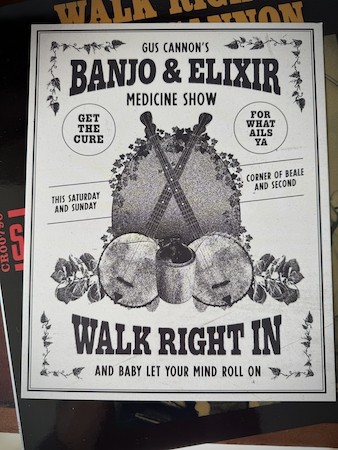

Cannon moved around the South as a young man, mostly in Mississippi and Tennessee. By 1907-08, he'd settled in Memphis and began playing music around time and for medicine shows, when he wasn't sharecropping or digging ditches.

The "early" Cannon recordings date from the 1920s, both under the name Banjo Joe and with his more famous Cannon's Jug Stompers. What's wild is these early recordings were likely done when Cannon was in his 50s. The fact that he was "discovered" in the 60s and then recorded the album I'm listening to right now sometimes in his 90s or early 100s makes you realize just how much amazing art we've missed.

There's a game classicists play: give up to get. We know of a ton of ancient works lost to us because they're referenced in works that have survived. The game is, what work that we do have would you give up to get one of the lost pieces? "Yeah dude, I would totally give up Atheneausus's Deipnosophistae for, like, even just one of Menander's lost plays!"

Me? I'd give up 95% of early 60s folk for 10% of the lost black blues and bluegrass of the 20s and 30s.

I'm pretty familiar with Cannon's Jug Stompers and Banjo Joe work, but this morning is the first time I've listened to this album, recorded in 1963. The fact that we have this record at all is thanks to a cover of the song "Walk Right In" that The Rooftop Singers took to #1 in 1962.

Around this time, the folk movement was "discovering" blues musicians like Son House, Robert Johnson, Mississippi John Hurt, etc., which were palatable given the acoustic guitar-driven tunes. Cannon was a bit tougher to adapt (despite having sold many, many more records back in their heyday) because of the centrality of the banjo. This one cover, though, breathed some life into Cannon's music career.

I'm fascinated by how musicians push and pull each other when playing different versions of the same song. Everybody knows the Oasis version of "Wonderwall." Ryan Adams released a cover that influenced the way Noel now plays the song. Trent Reznor now simply refuses to play "Hurt" after Johnny Cash's version, and Otis Redding famously said that "Respect" was "a song that a girl took away from me. Good friend of mine. This girl, she just took that song, but I'm still gonna do it anyway."

Listening to this album, I'm struck by how the Rooftop Singer's version of "Walk Right In" affected Cannon's version here. The original version has a different, more forward articulation of the main phrase, a more aggressive and catching cadence, while the '63 version mirrors the more mannered version of the Rooftop Singers. Further, Cannon follows lyric changes made by the Rooftop Singers! Their version sanitizes the song. Here's the Rooftop Singer's version:

Walk right in, sit right down

Daddy, let your mind roll on

Walk right in, sit right down

Daddy, let your mind roll on

Everybody's talkin' 'bout a new way of walkin'

Do you want to lose your mind?

Walk right in, sit right down

Daddy, let your mind roll on

But here's the original:

Walk right in, sit right down

And baby, let your mind roll on

Walk right in, stay a little while

But daddy, you can't stay too long

Now, everybody’s talking 'bout

That evil way of walking

Do you wanna lose your mind?

Walk right in, sit right down

And daddy let your mind roll on

Maybe it's just me, but those subtle changes to the lyrics make it a different song. Something different is happening in these two tales.

That man? That man knows what's going on in this song, and it doesn't belong in a church.

I've spun Walk Right In three times now, while writing this, and I should take it easy on my very patient wife. Let's hang the banjo up for the day. I find myself thinking about heritage, legacy, what's lost and retained.

More and more, as I'm working through a sudden and inescapable constriction of time, attention, and endurance, I'm focused on signal and noise, looking to find the next higher layer in the data > information > knowledge > wisdom pyramid.

Seek out the signal. Be relentless...if you can keep your eyes open and your focus trained.

Member discussion