OTR, Take 48: Talking Heads - Speaking in Tongues

Listen along on Tidal or Spotify.

I saw a Deadhead sticker on a Cadillac

I read this morning about the fascinating backstory of Don Henley's "The Boys of Summer," and you're lucky I don't have that record. In fact, I generally loathe The Eagles.

At the same time, I've always kinda liked "The Boys of Summer," what with that three-note descending signature synth part and the whispy guitar filigrees. That sad nostalgia that permeates the whole thing. The song was offered first to Tom Petty, who turned it down because the "jazzy" track didn't fit on the album the Heartbreakers were recording at the time, Southern Accents. And it was one of the very first songs to be built around a drum machine. For those in the know, Roger Linn was the mad genius behind the drum machine, and the drum track on "The Boys of Summer" was generated from one of Linn's early models – well before the famous Linn 9000 was introduced.

This is something of an exercise in how my week has gone: false starts, interesting but ultimately useless errata, avoidance of the Thing Itself, and helping others face their Things. Some weeks feel heavy: dense with layers of events, lessons, and labor that will take a while to unpack, to lay out on the table and examine.

Building big things – undertaking big projects – is a curious endeavor. On the one hand, I'm quite aware of the immensity of the lift. I'm almost a full quarter into this build and (to the extent any business endeavor is ever "completed") have another full two to three quarters left until v1 is completed. I know how much there is to do, and yet...there's that other hand grasping and grasping, furious that I haven't made more progress, that I don't feel closer to an end state.

This is one of the biggest risks in any significant endeavor: the obsessive focus on the next step blinds us to the work we've done and done well. It becomes nearly impossible to appreciate the progress we've made because there's always the next step to move on to. So we find ourselves forever focused on what's next, that endless line of tasks, of system builds, of drip campaigns, call scripts, document automation – and we don't take even a moment to look back and recognize how much ground we've covered.

My ADHD and business coach/minder, Marshall Lichty, stopped me a few weeks back and insisted I pause for a moment and acknowledge that I've made, by leaps and bounds, more progress on Purely Estates in the last four weeks than I made in the year and a half of its existence before now. I instinctively wanted to brush that off and refocus back on the work ahead. But he is right, and it's important to maintaining energy, focus, and morale.

We must acknowledge the gains made, celebrate the work accomplished, and then get back to it.

Fooled around enough with numbers

Let's not be ourselves today

The other day, a friend of mine asked me why I never write about my favorite bands on On the Record. I was somewhat dumbstruck; I'd just written about Frightened Rabbit and, while it's not a universal truth, if I own the record, I like the band. But that's not what he meant.

Specifically, he wanted to know why I haven't written much, if any, about Talking Heads or The National. (To a lesser extent early Modest Mouse and Radiohead.) And he's right: I haven't written much about Talking Heads or The National, and only a little about Modest Mouse, Radiohead, Mingus, etc.

I don't know, really, other than perhaps it's natural to hold the things you love closest. Am I the only one who finds it harder to write about something that is so embedded in your life, a direct part of your consciousness – the voices and words of David Byrne and Matt Berninger playing through my own thoughts and voice unconsciously? To write about these bands feels a bit like telling on myself and putting myself out for dissection.

"But Owen," you say, "you are endlessly – shamelessly – putting yourself out there for the world to see. You won't shut up." It may appear that way, but I can assure you, for as open as I am, I'm no different from most anyone else out here: I'm carefully curating how I'm presenting myself to all of you.

With that said, if you were to walk into my office or house, there's little doubt that, statistically, there's a higher chance of hearing Talking Heads or The National playing than nearly anything else. Maybe some Eno or Philip Glass in certain working moods.

So let's give this a go, shall we?

Watch out. You might get what you're after.

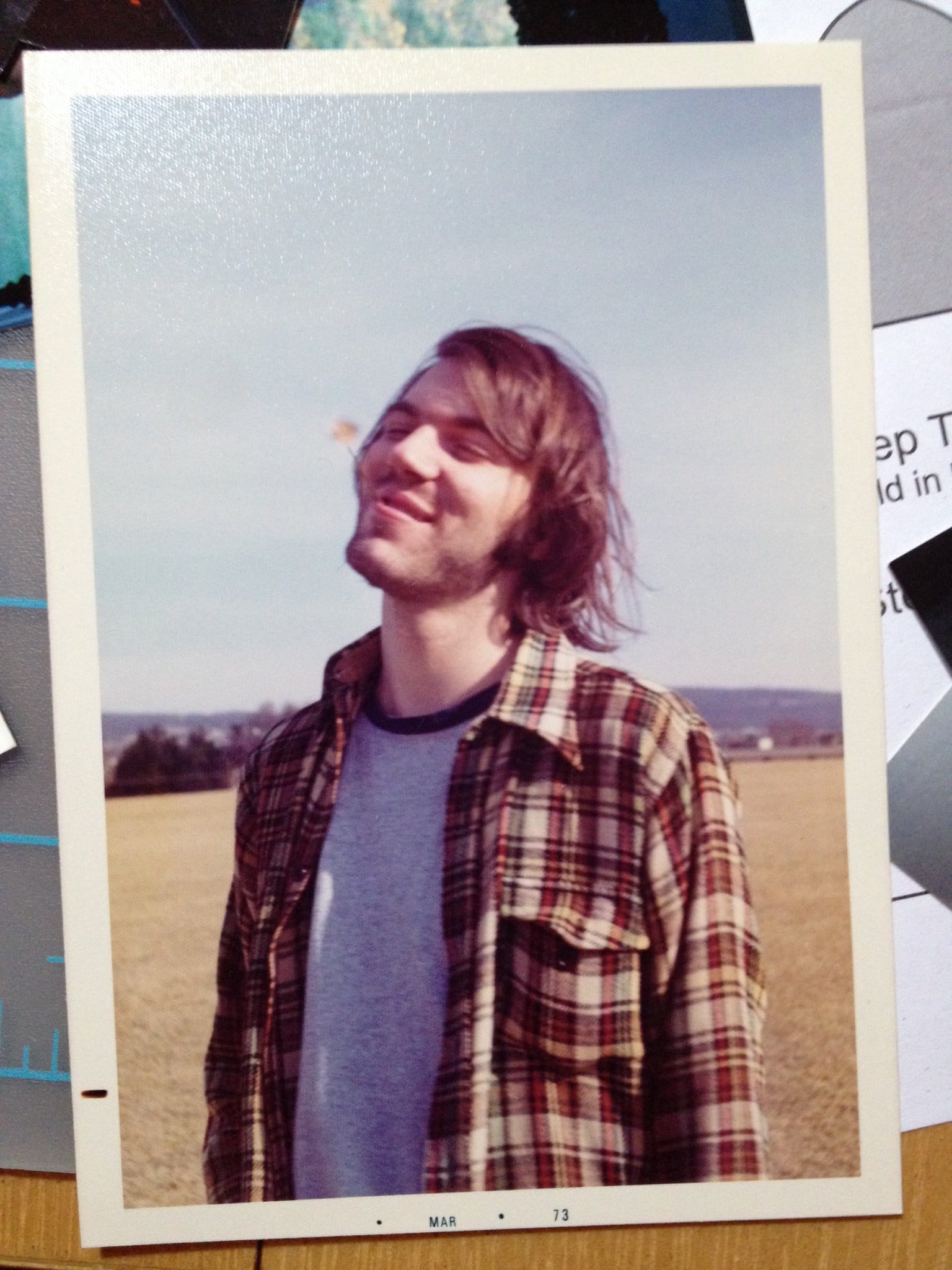

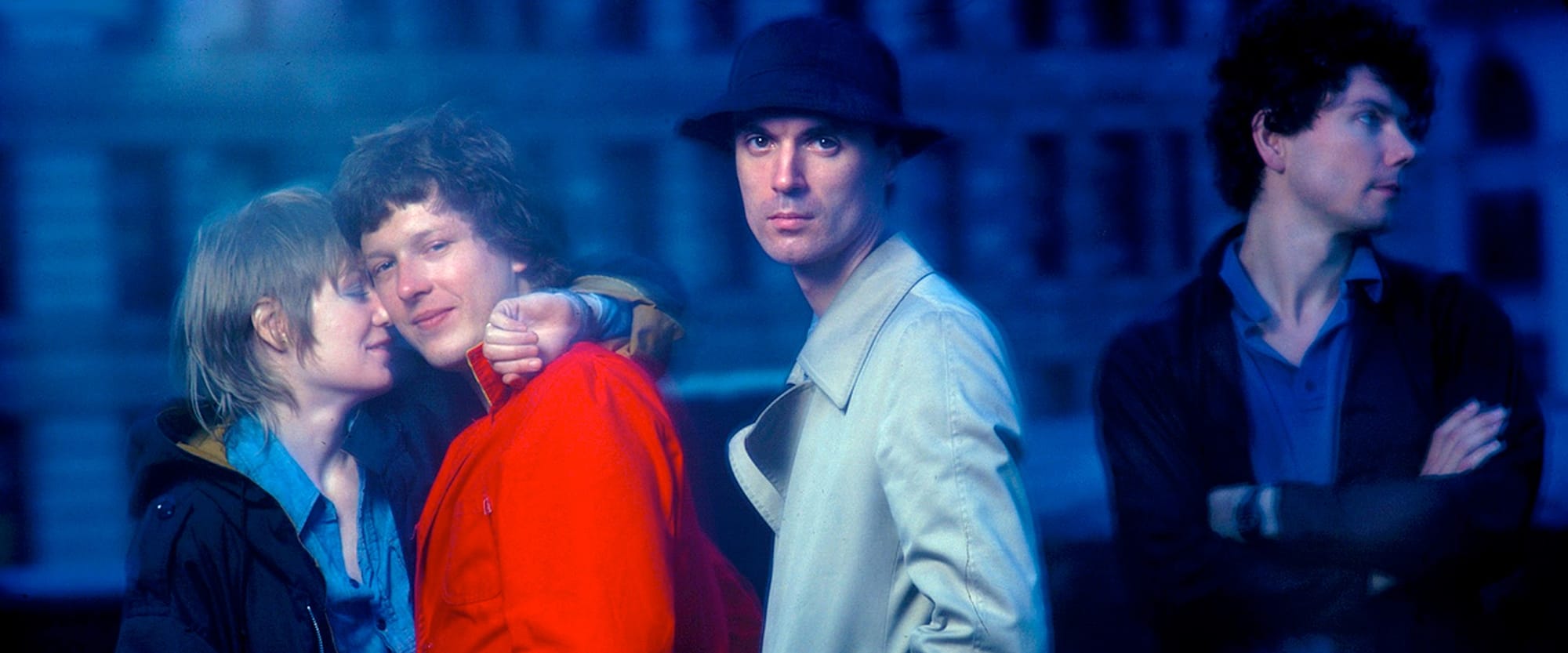

My father introduced me to Talking Heads in the early 90s. In 1993, at 12, I bought Green Day's Kerplunk! and got into "punk." I could swear I saw my dad's soul leave his body as I played Green Day for him and called it punk. It just up and left in one of my first vivid memories of seeing him go ghostfaced in the face of popular culture continuing to evolve beyond his very Boomer "The late 60s were the pinnacle of pop culture and everything that came after is decadent" attitude. I mean, look at the dude:

He sat me down and went digging through his records and pulled out some records, muttering something about CBGB. He dropped the needle on Talking Heads' 77 and said, "This is punk."

I'm going to shoot you straight, here: my immediate reaction was incredulity. Whatever Talking Heads was, it wasn't punk to my twelve-year-old sensibilities. Where were the power chords?! The faux British affectation? The puerile drug jokes?

But I did like it. A lot, despite the fact that I had no idea what it all meant. Now that I've lived with Talking Heads for 30 years, I can say with assurance that I continue to not know what it all means. But I know how it feels, and I've come to terms with the reality that art isn't meant to be pinned down so that we can say, "Ah, well, that's that. I guess we've solved that riddle!"

You might laugh but not for long

It's unfair to Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz, and Jerry Harrison to call David Byrne the man behind Talking Heads – each of the other members were and are wonderful musicians and artists in their own right – but it also wouldn't be untrue. Hearing Byrne's voice was the first time I realized that having an imperfect, limited voice could be a tremendous asset for a band.

We oooh and aaaaah over people with impeccable voices: Aretha, Sam Cooke, Whitney, Van Morrison, Christina, Freddy Mercury. But I've always been drawn to musicians with imperfections, whose sound is defined by the distinct limitation offered by an aspect of the band's repertoire.

Nobody would argue that Leonard Cohen has a classically great voice, but his voice defined his songs. The same can be said for Nick Cave, The National, Modest Mouse, and Talking Heads. At the end of Stop Making Sense, there's a bonus scene in which David Byrne interviews himself. He asks himself whether his voice is any good, and responds: "The better a singer's voice, the harder it is to believe what they're saying."

That has always stuck with me. This notion that the more polished and slick and perfect anything is, the harder it is to believe it. This winds itself into so much of what I do. Back when I played music, I was always interested in the fissure points, the moments where you can hear a hand move up or down the strings quickly and the sound of the instrument – not the sound the instrument makes – comes front and center. The moment when you can hear a drummer quietly counting out a pause before clamoring back in. The note that a singer reaches for that is just outside his or her range and you hear the voice break a little bit.

(Don Henley, after recording all of "The Boys of Summer" came in to listen to the mix and said, "I think we need to change the key to F#." That required re-recording everything except the programmed drums. Nobody was very happy about this, until they heard the vocal track, right at the top of Henley's range, bringing a note of desperation to the track.)

Byrne's voice is the quintessential example of this. He often sounds lost or rambling. An innocent fool walking through life making observations about things we've forgotten to see. A narrator of the world as it is without the gloss of our learned explanations.

You believe him because he's talking out your own thoughts without the shadow of artifice.

It's always showtime, here at the edge of the stage

Byrne was notoriously difficult to work with in the studio. An unrelenting and exacting composer of sonic landscapes. Talking Heads albums are just littered with interesting minutiae of sounds, packed in at the edges of the mix and sometimes hidden right down the middle of the track.

When everyone was ready to put a bow on a song or on an album, there was David, unsatisfied. Something was missing. Something extraneous was there, if only he could identify it. His bandmates would beg him to take it easy and he would torture them. Talking Heads broke up, officially, in 1991, but they'd been finished for years before then. It took years for several band members to speak with Byrne and they only recently got all together again – for A24's re-release of Stop Making Sense.

It's hard to argue with the results. To this day, nobody sounds like Talking Heads. Nobody can. From the way Byrne used his guitar as a percussive instrument (when everybody else uses it to, you know, play notes...) to the way punk mixed with funk, African polyrhythms, absurdist lyrics...there is no replicating the sound. Hell, Byrne can't quite recreate the sound. I've seen him live five times and he sounds like David Byrne, but even when playing Talking Heads songs, he and his band(s) don't sound like Talking Heads.

There's magic in that: recognizing the alchemy of a grouping of people. How many times have you wished you had a specific group you used to work with back together? Because the group, even if led by or dominated by one member, created something more than anyone could have created on his or her own.

Sometimes that magic can only happen for a specific period. Perhaps there's some wisdom in accepting the temporary nature of all wonderful things. They're more precious because of it, aren't they?

Cover up the blank spots

Hit me on the head

There's also a lesson in the fact that when Talking Heads broke up, none of the members simply gave up and stopped creating. Some of their projects are as or more dear to them than Talking Heads, even if those projects did not catch our attention in the same way. (I'm particularly fond of Byrne's very weird and fascinating books.)

One of the aspects of the business I'm building that I've been thinking about a lot is this attempt to create a business where people can come and go, plug into defined roles, and unplug when it's time. In a perfect business world, you'd design this to be plug-and-play. The people fit in, perform the defined tasks, and that's that.

I've spent a lot of time creating these structures, roles, and workflows over the past two and a half months. One of the things that sticks in my craw, though, is this: if the most meaningful things to me require a bit of a raw edge, a series of imperfect pieces that combine into something better than the pieces, why am I trying to create a plug-and-play structure?

Ultimately, it's a give-and-take here, right? The structure, the workflows, the processes and roles, gesture toward the form of the business. But the people matter. And each addition, each loss, each moment of growth recreates the firm anew in some respect. The goal isn't to create a static thing. What fun would that be.

We must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Member discussion