A Poorer Place

Nota bene: I had intended on releasing an OTR today on A Charlie Brown Christmas, but news yesterday set me on a different path. This may not be Christmas reading. Or it may be. YMMV.

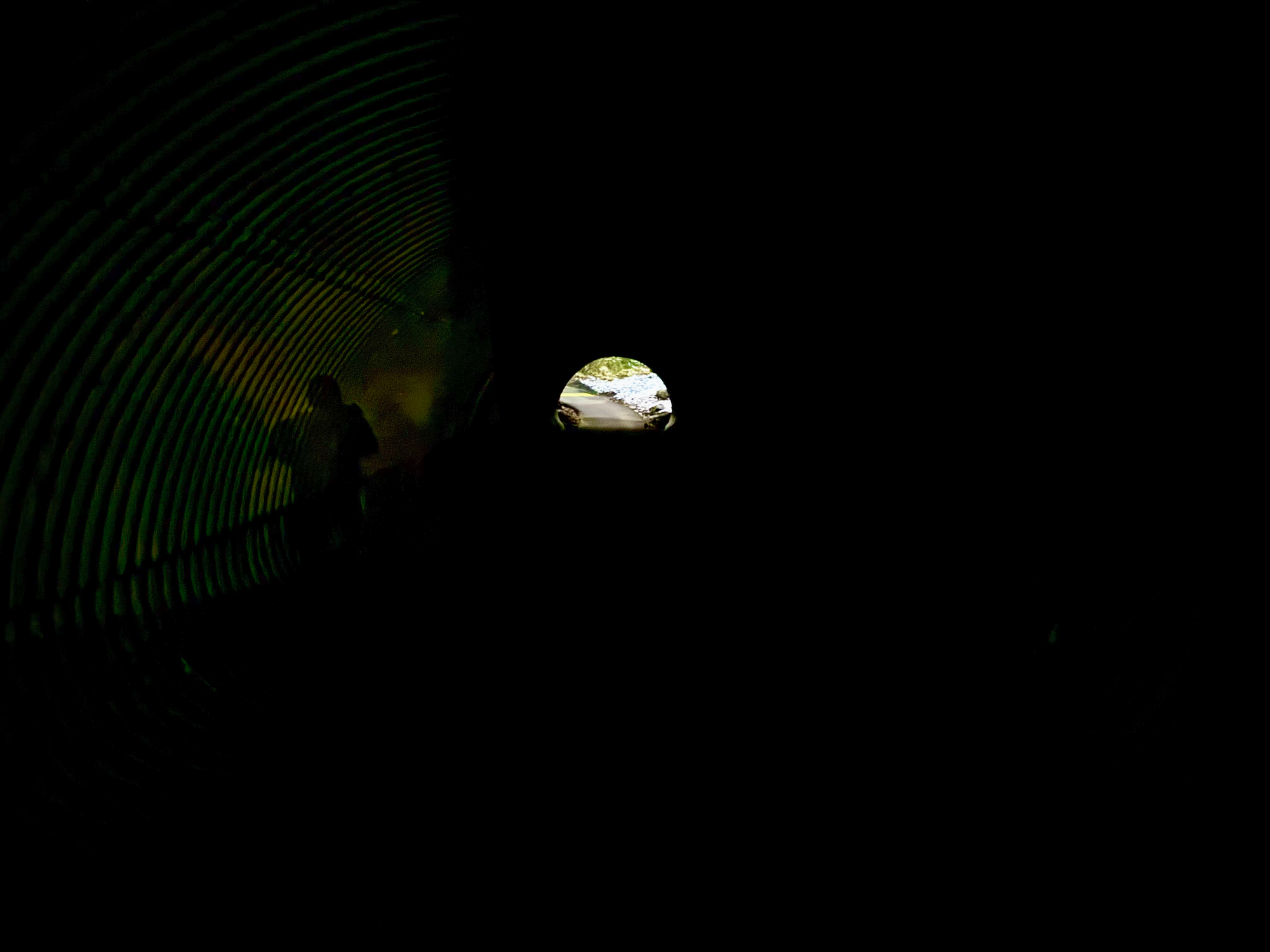

There's a corrugated steel tunnel not far from my house I like to walk to at night when I'm feeling down. It's about a mile walk along a path that runs beside a country road that has been engulfed by suburbia. The path is lined with tall, arching trees planted about 100 years ago by – no joke – the Trees family, which owned a massive apple orchard named Treesdale. That orchard is now a country club of the same name.

Things change. Inevitably. Even when you imagine things to be stable, maybe even permanent. Life marches on, grafting new layers on a palimpsest we never quite take the time to decipher.

I like to go to this tunnel because in the dark of night, it shows that things can get yet darker. Clare is nervous to enter the tunnel, probably for the very reason I like going: when you enter, you can't see where you're going. You can't look down to find your footing, because you cannot see the ground or your feet. You walk through with the assumption that you'll make it through, that the path is clear. That you won't tumble ass over teakettle on a stray rock or random obstacle.

It centers me on a simple fact: our lives are uncertain and we walk through them mostly blind, all while assuming we'll hit the other side of the tunnel. We get so used to how unmoored we are that it takes effort to confront the absurdity of our existence. So many of us behave as though we are in control of things. We suffer from a kind of OCD that blocks out any semblance of uncertainty. We seek religion or science or philosophy or booze to mask the fact that we are naked primates in the scheme of things, at the utter mercy of entropy.

So I go to the tunnel when I begin to feel like I am out of control with grief or melancholy to remind myself that I am and have always been out of control, that seeking control is addressing the wrong problem in the first place. That seeking control is an assertion of the ego and the only way through is ego death.

I spent some time at the tunnel last night. A friend texted me yesterday afternoon and, thinking it was a kind "Merry Christmas!" message, I opened my phone unprepared for what greeted me: a link to the obituary of a man I loved and love still.

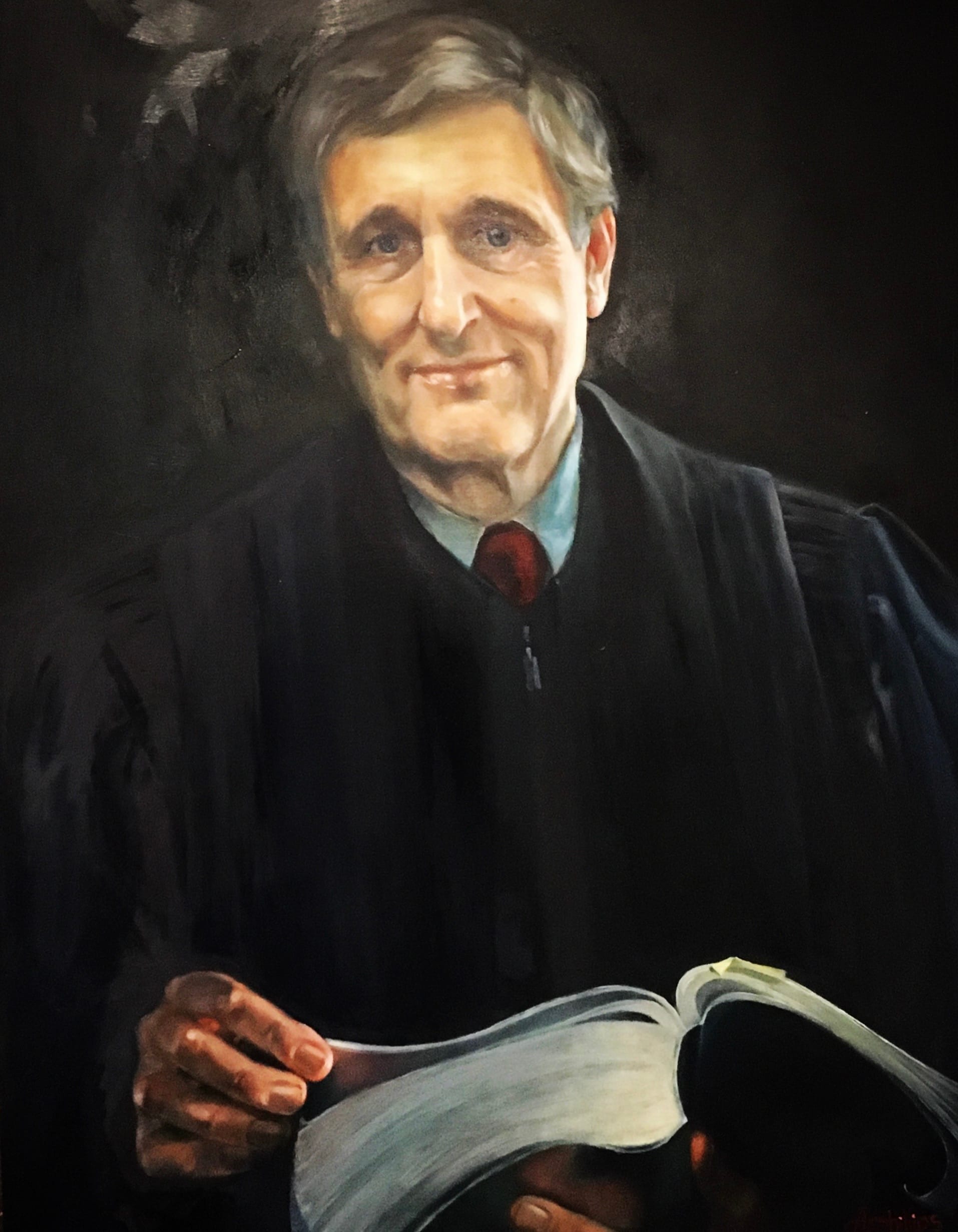

On December 21, 2024, one of my mentors, a man who cared about me more than I had any right to expect, returned to nothingness. The spark of consciousness snuffed out. I don't want to dwell on the return to nothingness here (my own spiraling thoughts are plenty to work through), but I do want to celebrate a man I called Judge Wettick or Your Honor no matter how many times he asked me to call him Tony.

I was his second choice.

In the spring of 2009, Judge Wettick interviewed several potential clerks to work alongside his permanent clerk, Cathy Gerhold. He selected his rotating clerk from students who took his PA Practice course at Pitt Law and clerking for him was the only state-level clerkship in Pittsburgh that held the same kind of prestige as a federal clerkship.

Keep in mind this was spring 2009: Obama had just taken office and the recession he inherited was wreaking havoc on the job market. There weren't exactly a ton of opportunities. Firms were laying off associates, not hiring them. So when I learned I was a finalist for Judge Wettick's position, I was thrilled. I knew how much it paid ($38,000), but also knew that it paid and that working in his chambers would be a tremendous opportunity.

Near the end of my year with him, he let slip that I had been his second choice for the role. I suspect he saw a little twinge of sadness on my face.

"I knew you would be fine, Owen, one way or another."

He wasn't wrong. But I did get the job and it was the best I've ever had.

He was the first person in the legal world who sniffed out that I wasn't like most of the folks in the profession. He was also the first person who told me that I could be a great trial lawyer but that didn't mean I had to do it.

I'd never given him any indication that I wanted to do anything other than be a trial or appellate litigator. But he knew, and told me in his indelible way: "Perhaps the world would be a poorer place if you pursued that path."

Tony Wettick saw me before I dared to see myself and fought for me, insisted on pulling me into the light so I could better see.

"I wish you could see how your eyes go wild when you talk about literature. You come alive. When you talk about law, your eyes slint and focus: it's a piercing vision, but if you can see wide and far..."

He cared about the people around him deeply, with the mature love that understands and accepts shortcomings – and makes you want to do better. How many revered figures do you know who talk about nothing and nobody but him- or herself? I don't begrudge folks who find themselves to be fascinating subjects (obviously), but there is an effortless grace that some people have, projecting an unaffected care for others.

The people who ask, "How are you?" and mean it, who won't let you off the hook when you say, "I'm okay."

In late February 2018, I came within a minute or two of dying on the operating table. Prognosis going forward? Not great. A few days after the surgery, Audra and I were sitting in UPMC Shadyside as she graded lab reports and I pretended to read. (I wasn't able to focus my eyes on the words.) She turned to me and said, "I don't want you to die before I'm able to marry you. Would you marry me now?"

This woman is crazy.

Yes I said yes I will Yes.

"Okay, how do we make this happen?"

When I was discharged, I called Judge Wettick. I told him the situation and asked him if he would officiate our wedding. He didn't let me finish: "Just tell me when and where." Audra and I met Judge Wettick and his wonderful wife, Nancy, at Pointe Brugge on a Friday night in March, had moules frites, got married, and talked about medicine and T.S. Eliot.

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;

Let us go, through certain half-deserted streets,

The muttering retreats

Of restless nights in one-night cheap hotels

And sawdust restaurants with oyster-shells:

Streets that follow like a tedious argument

Of insidious intent

To lead you to an overwhelming question ...

Later in 2018, I received the diagnosis that put me on the formal path toward an organ transplant. I called Judge Wettick and asked if we could get lunch. There are some people you go to in the most difficult times.

I remember parking along Penn Ave and meeting him in his retirement office at Neighborhood Legal Services. He was not one to stop working just because Pennsylvania has a mandatory retirement age for judges: he went back to NLS where he caused such trouble, the governor decided to put him on the bench.

We went to a local restaurant and sat in a booth. I began sketching out for him my idea for what became one of my firms. He humored me for a little while, before interrupting.

"Owen, it's great that you want to go out on your own and try something different, but that's not why you asked me to lunch."

So I told him and he sat with it for a minute.

"Are the doctors sure?"

They are, with a painful biopsy and all kinds of expensive tests to confirm.

"How old are you?"

37 years old.

"It's not fair. You're too young."

I told him I had to approach it thinking that I'm lucky to be alive at a time when organ transplants are possible. He shook his head the entire time I was saying this to him. The man who had spent 40 years on the bench doing his damndest to mete out justice could not tolerate what seemed so manifestly unfair.

"Your Honor: I have to accept this situation to get through it."

"Fine. I'll be angry for both of us!"

As much as anyone I've known, Judge Wettick lived a full life. He was active in his community, had many friends and somehow found time for us, was the paragon of what we hope our jurists to be, and loved his family dearly.

While transiting through that tunnel last night, I couldn't help but think how disappointed he must be in me for not doing enough. But I know that's not true: he was proud of me. After my transplant on January 22, 2020, the first call I received was from Judge Wettick. He left me a voicemail on January 23rd at 9:30 am. I still have that voicemail.

"Hi Owen, it's Tony Wettick. I hear you've had a hell of a night. Give me a call when you feel up to it. Thinking of you."

Simple and to the point. As always. When I called him back a day or two later, still with the giant central line sticking out of my neck, I could barely speak. I'd been intubated and had no strength. I whispered as much as I spoke.

Never one for small talk, he said he was happy to hear from my dad that the surgery went well but he was sorry I needed it in the first place. And then: "What books do you need?"

I thanked him and told him I was getting better and was determined get back to full health. I told him how much it meant that he reached out and that I was a lucky man to be alive and surrounded by wonderful people.

Again, that stubborn sense of justice kicked in.

"You are not lucky. I refuse to accept that."

But I am a lucky man. I am alive, for now, despite everything. I have rebuilt my life in the shape of something that suits me. And I was able to call Tony Wettick my friend.

I'm about to head over to my parents' for Christmas dinner and will put on a brave face so my mom has the Christmas celebration she desires. But that tunnel? It's on the way home and I think Clare and I will be making the walk.

Thank you for reading if you've made it this far. Tony Wettick is a man I wish you could have known, if you didn't. The best among us. The world is a poorer place now that he has left us. Now it's up to us to make up for it. Let's call one more person, reach out to that friend you've been meaning to hit up, take the time to do something meaningful for yourself or your family. We have only a short time on this earth. What will you do with it?

Member discussion